As a class we have looked at a variety of different electronic works, including self-generating texts, e-literature, and e-poetry in our digital humanities course with Dr. Justus. In this part of the course, we've started to learn about different types of interactive games. This has led us to question, do games count as scholarly works that can be researched/created by DHers?

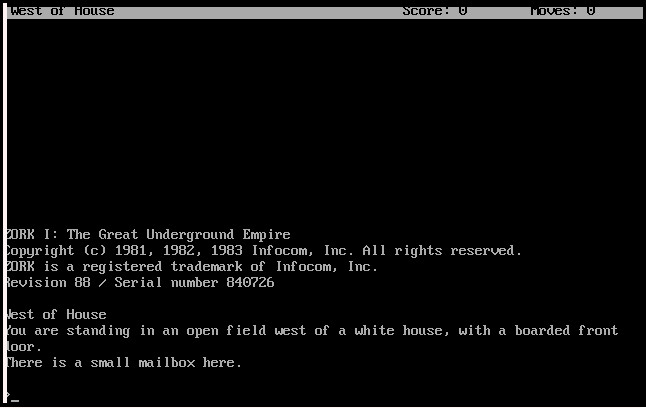

When you think of games, you think of exciting plot lines, getting to make your own decisions, and just fun in general. This describes the interactive computer game “Zork” to a T. Basically, Zork is an interactive story, plot line, game where you are guided by instructions and key words but you have full control of your fate in the game. For example, in the game the main goal is to get inside the white house so you can continue the story. Right when you walk inside the house the room is described to you and there are things you are able to pick up and keep for future use. Well, you get in the house through the window into the kitchen and there are various items you are able to take, food being one of them. Here is where a very important aspect of the game is. If you blow past the food and try to continue on with the game, later on in the game you will not have enough energy to complete a task, resulting in losing the game. Where as, if you take the time to eat the food then you will have enough energy throughout the story. Zork is a fun game for anyone to play and figure out. It does not have any hidden meanings and is not about a heavy subject like other works, however, it is just as respectable as any other piece of e-literature because of the intricate plot line and interactiveness for the player.

Games usually stem along the line of wanting to provide players with a specific kind of experience. These experiences are usually based upon the nature of the game, and the genre it uses to label itself as. I like to look at games differently, instead of looking at them as their labels (the genres) I tend to look for two aspects. Entertainment and Education. This characterization obviously relies on a spectrum between these two statements. However, I’ve found that these two labels really help to establish how much a person is going to get out of the game. For example, Maybe Make Some Change was a game designed with an unquestionable amount of education involved in the production, with entertainment being put on the back-end of its completed design. This “game” I’d even stretch to call it, was devised in order to retell the events of past in order to educate the player on a real-life event they’d probably never heard of before. It’s usually in a games best interest to captivate its player-base in one way or another, and majority of the time it involves plenty of topics, from: graphics, replayability, narrative, gameplay, control schemes, soundtracks, leading up to the game, and sometimes even the designers of the game. However, as stated previously, majority of the enjoyment from a player-base is how honestly a game expresses its intentions, entertainment or education.

This is where the discussion of the game should take place. On the topic of how honestly the creators of the game decided to express that within this more arguably education game than an entertaining one. The genius behind its creation is not in the narrative however. The genius stems from how they produce the replayability within the game. Usually, a producer aims to make a game more replayable in the interest of the business for the game, and to lure players into investing more time to be spent within the game. Maybe Make Some Change somehow seems to do the opposite. Its replayability is tedious and exhausting and from what I’ve observed, leaves players from wanting to even finish the game in the first place. This allows for two things to happen for players to experience the greatest part of the game early on, and to create discussion revolving the game itself. For a game revolving around education, this combination is perfect, because it allows players to experience the best part of the game early on, without having to spend extra time into the game, while also providing easy discussion once having finished spending time on the game. However, there is one more thing to add to the equation, and that would be the reward for those who are dedicated to replaying something deemed replayable. Those who wish to invest more time into the game begin to reveal the puzzles and secrets about the game that would otherwise be unobtainable to those without the effort to attempt this feat. As an educational game, MMSC does a great job of providing short-term enjoyability from those not willing to put a lot of effort into a game, but also does a great job at rewarding those who are willing to invest into it. This provides for an emotional, rewarding, and controversial narrative, ultimately a great experience when it comes to games. The player is taken on a journey that confuses them, but rewards the confusion with slight moments of achievement with the intention of driving further investment into the game with more words being accessible to the player.

This ultimately provides the timeline of confusing the player → rewarding the player → confusing the player some more → rewarding some more → testing their problem solving skills → resulting in either failure to continue playing or more investment into the game → for the latter, the player continues to play, ultimately getting frustrated and angry with continued failure, but a sense of perseverance and an unwillingness to give up in order to achieve total completion. → This is then rewarded by further insight to the narrative, and then the final reward being the full story leading to the creation of the game itself. The producer allowing insight to their game, can arguably be one of the greatest achievement because it allows the player to feel connected to the creation of the game. It allows the player to feel responsible for the creation of the game in the first place. Regardless of the game, it delves into the notion that the producer created the game personally for the person who was willing to complete the game. This, in-turn, is the success behind why an educational, and narrative driven game like MMSC, into being a genius creation.

This ultimately provides the timeline of confusing the player → rewarding the player → confusing the player some more → rewarding some more → testing their problem solving skills → resulting in either failure to continue playing or more investment into the game → for the latter, the player continues to play, ultimately getting frustrated and angry with continued failure, but a sense of perseverance and an unwillingness to give up in order to achieve total completion. → This is then rewarded by further insight to the narrative, and then the final reward being the full story leading to the creation of the game itself. The producer allowing insight to their game, can arguably be one of the greatest achievement because it allows the player to feel connected to the creation of the game. It allows the player to feel responsible for the creation of the game in the first place. Regardless of the game, it delves into the notion that the producer created the game personally for the person who was willing to complete the game. This, in-turn, is the success behind why an educational, and narrative driven game like MMSC, into being a genius creation.

After looking at these different pieces of electronic works, you can see that we came to the conclusion that games do count as scholarly works that can be researched / created by DHers. These games all include their own plot line, users get to make their own decision, they’re interactive, and more qualities that basic, real games include.

No comments:

Post a Comment